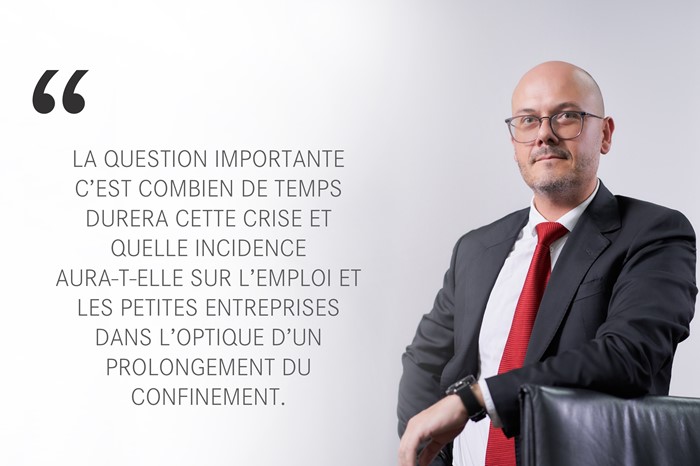

The least one can say today is that the world is going through a deep economic crisis. Is this due entirely to COVID-19, or was the virus just the last straw?

The world has been at the edge of a tipping point for over a year, considering that global debt was already at record-breaking levels before the crisis began. The spread of COVID-19 disease was the unpredicted event that toppled markets, closed businesses and borders, made working-from-home the norm and brought global activities to a standstill. While this started as a sanitary crisis, its repercussions have cascaded to the overall global economy, resulting in a multidimensional crisis. We also know that if countries reopen their economies and borders too quickly, there will be a second wave of the pandemic. This can derail everything we have done so far and potentially set off a new outbreak even before this current situation is under control. It will definitely prolong the economic recovery and the impact and consequences of a second wave would be devastating to the global economy.

What is the situation in Mauritius where our debt was already in the 70% region, according to several economists? Are we heading for a recession?

Yes, a recession is underway. Until there is a better sense of when and how the COVID-19 public-health crisis will be resolved, economists cannot even begin to predict when it is going to end. Still, there is every reason to anticipate that this downturn will be far deeper and longer than that of the 2008 Financial Crisis. As a result, in its report dated 20th April, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasted the global economy to contract sharply to -3%. With regards to Mauritius, the economic performance is estimated to shrink to -7% this year. It is important to note that these estimates can deteriorate further with the possibility of a second wave if we are not cautious and reopen too quickly. The situation in Mauritius will remain dependent on what happens globally, especially for our key markets.

What will be the impact on banks?

Like several sectors, the banking industry has witnessed an escalation of different risks. These are both direct “on balance sheet” risks such as credit and liquidity risks as well as operational risks, cybersecurity and “off- balance sheet” risks. Banks’ Chief Risk Officers (CROs) will have a key role to play in managing these risks and are going to be stressed-out at the moment with the review of risk appetites and risk management strategies. Executive teams and board risk committees need to strike the right balance between prudently extending credit to serve their clients and maintaining the liquidity and capital ratios.

Concretely, does that mean that it will be difficult to get credit from a bank these days?

More than ever, during this crisis, governments are using banks as a transmission mechanism to implement their support and relief measures. Risk and Credit officers will have the difficult task of assessing whether clients will be financially robust when these support programmes are exhausted and in the event we have a prolonged impact of the crisis. Therefore, banks will have to do detail case-by-case assessments of their clients and their cash flow requirements to prevent these clients from going into default. For many sectors, it will definitely take some time before normal business activities thrive again, which potentially may have a long-term impact on banks and on the economy at large. Consequently, banks will need to intelligently balance their risks between protecting themselves as well as extending support to the economy in a context where both are connected and correlated.

Since most Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) are in great financial difficulty, does the fact that banks will be more cautious in their lending not sound the death knell for them?

Banks will need to work with businesses to figure out the best course of action, including tactical and near-term strategic business moves, to limit more aggravated impact on the bank and the economy in the future. Some tough decisions will need to be taken by banks to protect themselves. In Mauritius, like many other countries, the most impacted industries are the tourism, aviation, construction, property industries and SMEs. These industries are highly dependent on other countries and with the low market sentiment and the rising unemployment rate globally, business activities for many sectors are expected to have a slow recovery.

SMEs will also have to reinvent themselves. During these challenging times, they can leverage on the current economic dynamics to induce a shift in consumption from imported goods to Mauritian products. In the coming months, consumers worldwide will become more conscientious spenders and this can be taken advantage by our SME sector.

Moreover, loans to the impacted sectors will need to be restructured and rescheduled to match revised and impacted cash flows. This process will prevent defaults, hence supporting these industries as well as giving banks a breathing space in terms of extending the time frame to raise provision. The expectation will of course be that most of the impacted loans will be cured once the economy normalises.

However, banks will come under pressure over time as there is a risk that some of their loans will go into administration and liquidation due to permanent damages to certain borrowers. Most banks have already started to analyse this impact on their capital and liquidity ratios. Consequently, it is important for banks to keep sight of both the first-order and second-order risks. Practically speaking, in my view, the right response should come from risk experts who should embrace the crisis and learn to re-adapt by re-assessing modelling scenarios and understanding their implications on earnings/revenues and potential credit losses of these clients. Forecasting exercises should be dynamic because the situation is changing very rapidly.

The Bank of Mauritius has set up a number of measures to help banks stay afloat. How will clients indirectly benefit from these?

The Bank of Mauritius (BoM) like many other countries has put in place Governmental Support Programmes for sectors being affected by the crisis. These support programmes will enable banks to sustain their clients by allowing for moratoriums. The moratoriums announced by BoM are deferments of the repayment of capital and interest on loans for a specified period of time. These moratoriums aim at temporarily alleviating the financial constraints of those businesses, households and individuals currently experiencing difficulties over the scheduled repayment of loans as a direct result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Additionally, under the special relief programme, the interest rate on advances to impacted economic operators was initially capped by the BoM at the fixed rate of 2.50% per annum. However, now it stands at 1.50% per annum following a decision taken on Thursday 16th April 2020 by the Monetary Policy Committee to reduce the Key Repo Rate by 100 basis points to 1.85%. This initiative intends to reduce cost of debt and alleviate the stress on the cash flows of impacted sectors.

Isn’t the BoM itself suffering from a lack of liquidity after the Rs19 billion transferred to the government?

It is important that we differentiate between a transfer from the BoM reserve account to the government and the liquidity available in the system to fund this crisis. In fact, if we look at the cash reserve ratio for the reporting period 30th April 2020, the excess liquidity had almost doubled compared to the prior year’s average.

In the financial year 2018-19, the BoM had an annual average rupee excess reserves of Rs.12.2 billion from banks, which was 50% more than the previous financial year (Rs.8 billion). This excess rupee liquidity nearly doubled to Rs.24 billion in the fortnight ending 24 April 2020. The prevalent situation of excess liquidity in this market has partly been driven by the average deposit base growing faster than the credits over the past few years.

A debate is ranging around ‘Helicopter money’. Where do you stand in this? To print or not to print?

Helicopter money refers to a large sum of new money that is printed by the central bank and distributed among the public in order to stimulate the economy during a recession or when interest rates fall to zero. Even though theoretically Helicopter money aims to boost consumer spending and thereby stimulate the economy, its implementation in real-life is questionable.

As it is often said that there is no such thing as a free lunch. The problem of newly printed cash is that it can lead to a devaluation of the currency and fuel a risk of inflation. Converting the central bank into a magical money tree could lead to a significant currency devaluation on the foreign exchange market. As more money is printed, the money supply is increased in the economy and hence, the value of the domestic currency could significantly decrease. In the Mauritian context, we have already seen that the USD/MUR has already reached the Rs.40 mark. With a Helicopter drop, our currency could further devaluate, which can lead to a potential decrease in foreign direct investment (FDI) as investors move to other jurisdictions with a stronger currency.

Besides, since the money is directly distributed to the public, it can cause damage to the central bank’s financials by interfering or making monetary policy less effective. Helicopter money also can give rise to inflation and together with the devaluation of the currency, there is a risk of spike in the price of basics necessities like food and other commodities. Hence in my opinion, for the time being, quantitative easing is more appropriate for the current crisis.

You talked about the risk of outflows of foreign currency a serious threat to banks and to the economy if our currency is devalued further. Isn’t that a very dangerous thing for Mauritius considering the large deposits of transferable FDI we have?

Mauritian banks combined have approximatively Rs.700 billion of deposits, out of which 80% are either Transferrable or on Call. There is no risk of any outflow for the moment but it will all depend on the lasting impact of the crisis and the liquidity requirement of foreign investors coupled with their confidence in Mauritius as a robust and stable International Finance Centre (IFC).

How robust are the banks?

As per the regulatory guidelines, it is essential that banks have adequate High Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) in order to stay resilient during this time of crisis and to be able to meet their liquidity requirements for a 30 days’ liquidity stress period.

Since one of the primary objectives for banks is to protect their depositors’ money, banks will have to demonstrate robust liquidity and capital ratios to boost investor confidence. While the aim will be to de-risk the balance sheet and show robust ratios, they will also need to be transparent and not hide losses; surprises only worsen investors’ response, as proven during the 2008 crisis.

How are banks finding the new Work-from-Home Culture?

The daily operations of banks have significantly changed during lockdown. Business Continuity Planning has been put to test and most of the banks’ personnel are working from home. This means that IT security systems had to be enhanced to prevent heightened risk of cyber-attacks and the increased compliance risks due to the change in working practices are already causing headaches such as increasing market abuse risk while working from home.

Since the lockdown, banks’ business model has evolved. There has been a rise in the digitalization of services and banks will need to revise their strategy accordingly to remain relevant. With the widespread adoption of e-banking and the spread of smart devices, banks will need to provide innovative customized services and understand customer’s financial need in order to provide better assistance.

A local bank has already gone belly-up. How many of the other banks we have on the island have the wherewithal to survive this crisis?

From an industry perspective, banks are more resilient both in terms of capital and liquidity as post the 2008 Financial Crisis, there were pressure to strengthen the regulation, supervision and risk management of banks. However, post-COVID will be a new era for the economy and banks will need to be proactive rather than reactive. Banks are managing and focusing on how to stay resilient after this crisis. In the pursuit of higher returns, they sometimes over- leverage themselves on high yielding bonds or liquidity mismatch beyond their capacity. In times of crisis, a number of these bonds and assets can default impacting profitability, capital and liquidity of banks. Post-COVID-will undoubtedly give rise to a “new normal” and we should be ready to adapt and prosper in this unparalleled environment!